Few notions among those who do business in India are perhaps as pervasive and deeply held as the one about doing business with the government. It’s a bit like a visit to the dentist — best avoided, but if you must, then pain and unpleasantness can’t be escaped. Complex procurement norms, bureaucratic hurdles, nepotism and delayed payments make it an affair that requires grit.

Few notions among those who do business in India are perhaps as pervasive and deeply held as the one about doing business with the government. It’s a bit like a visit to the dentist — best avoided, but if you must, then pain and unpleasantness can’t be escaped. Complex procurement norms, bureaucratic hurdles, nepotism and delayed payments make it an affair that requires grit.Entrepreneur Shweta Sharma, 27, harboured similar notions, too. Started by three college friends in 2016, her startup Leaf Era sells moringa leaf tea and extracts. They started retailing on Amazon and Flipkart and now exports to Hong Kong. Late last year, her entrepreneur father, who runs a sanitary fittings business, suggested something that made her raise her eyebrows. Start selling on GeM, or the Government e-Marketplace (gem.gov.in), he said. Doing business with the government has become easier and safer, with timely payment and few logistical hassles. Sharma was sceptical.

But within days, she changed her views. Onboarding the GeM platform was easy, with all registration formalities, such as uploading documents and their verification, done remotely in two days. Within a month, Leaf Era was selling on GeM. Under the Womaniya platform (a government initiative to encourage women-led startups), her vendor assessment fee was waived. “The GeM team was very supportive and motivating,” she says. Since hers was a “non-traditional” product, GeM executives helped out by sending emails to government departments, letting them know about it.

“That’s how I got Indian Railways Catering and Tourism Corporation (IRCTC) as our customer. Their office now stocks our products,” she says. Her monthly sales have grown from Rs 5,000 last October to Rs 1 lakh now. Up to a tenth comes from the government. “Payments have always been on time. I would have never imagined that doing business with the government can be so smooth,” she says. Now, she is targeting other government departments such as the military.

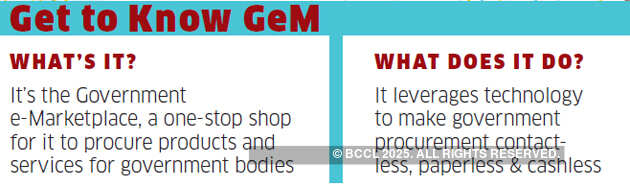

Leaf Era is one of the growing number of vendors on the GeM platform that is revolutionising procurement by the government. Rolled out by the NDA government in 2016, GeM is an e-commerce platform launched with the ambition to make government procurement cashless, contact-less and paperless — an Amazon for the sarkar, if you will. Replacing archaic, bloated, filedriven DGS&D (Directorate General of Supplies and Disposals) with a staff of more than 1,800, the lean, tech-led GeM has just 50 employees. It has had an impressive journey, digitising government procurement. It could easily qualify among the fastest scale-ups of an e-commerce platform in India.

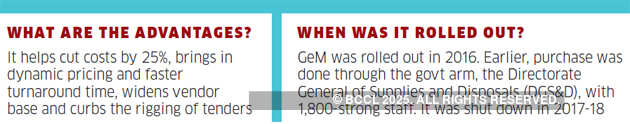

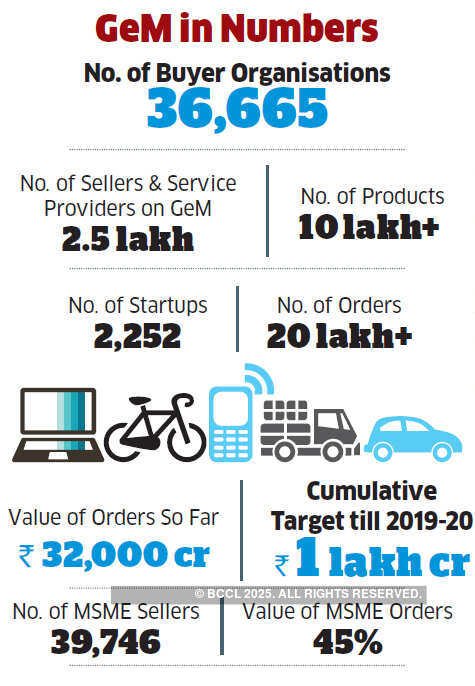

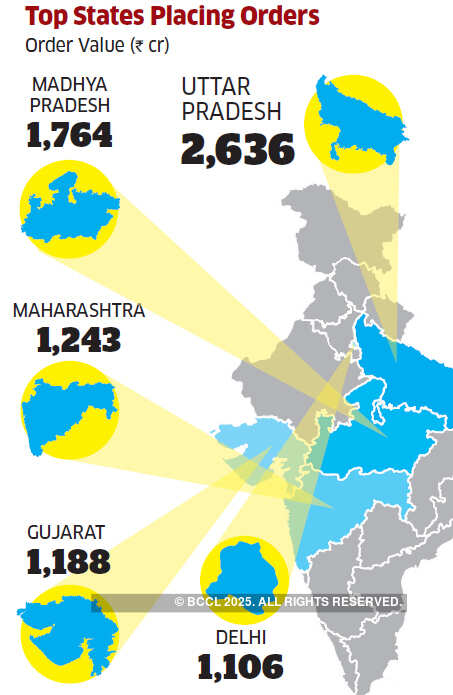

Today, it has 2.5 lakh registered vendors and about 37,000 buyer organisations, including government departments. About 200-plus public sector units (PSUs) and 30-odd states and Union territories have been brought on board. It offers 10 lakh-plus products and 12,798 services. Since 2016, it has managed to do transactions worth Rs 32,000 crore. It is targeting to take the cumulative total to Rs 1 lakh crore in 2019-20. “We are growing well. Since we were late in digitising procurement, we managed to leapfrog and now offer both products and services on GeM, a unique feature globally,” says Radha S Chauhan, CEO, GeM.

Using technology to deliver faster, cheaper and efficient citizen services has been the Narendra Modi government’s mantra. GeM rollout deploys the same strategy in the government.

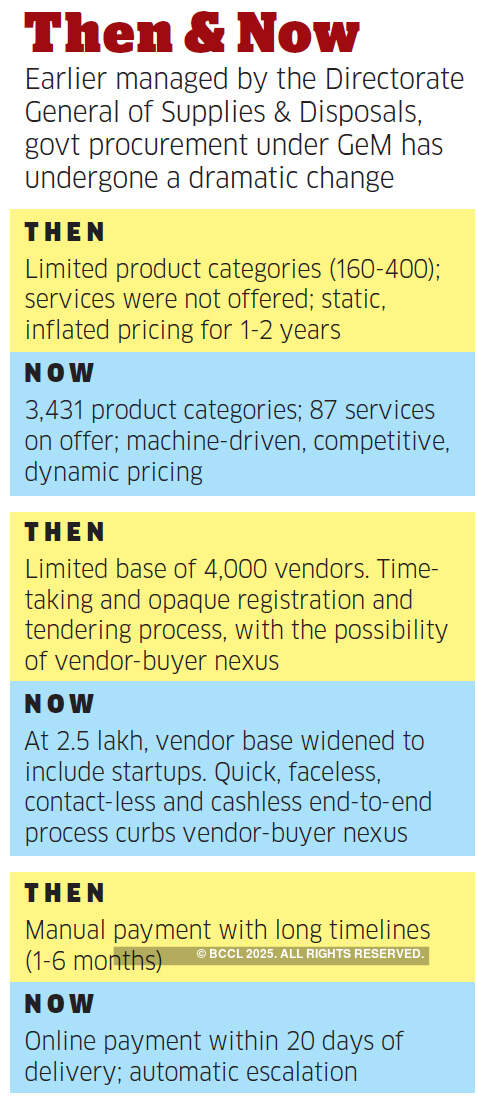

By any yardstick, as a buyer, the government’s budget is huge. Typically, its procurement is 5 per cent of GDP, which stood at Rs 190 lakh crore in 2018-19. About 40 per cent of the procurement spend is on buying products (including office stationery and laptops) while the rest is on services (like cab services and housekeeping). Till around 2016, it was mostly done on paper, with archaic bureaucratic procedures that were inefficient, time-consuming and opaque, leaving enough headroom to rig the system. With GeM, the ecommerce wave that has changed the way Indians buy is now altering the way the government shops.

India is part of the global wave. In 2016, McKinsey put out a report that estimated that “government digitisation using current technology could generate over $1 trillion annually worldwide”. In 2011, Bangladesh, which spends around $10 billion in public procurement annually, launched its e-GP (electronic government procurement portal) to allocate public funds more effectively and transparently.

Singapore started its journey even earlier in 1998 with GeBIZ as a “one-stop, non-stop” online centre for public sector procurement. Its public procurement programme is now moving on to the next phase, trying to enable more complex engagement with businesses like dynamic contracting, trial experimentation and co-development with business partners.

The Journey

Until 2016, government procurement in India belonged to the analog world, with DGS&D being the sole authority to fix both rates and specifications for every product.

With manual procedures like physical verification, it would typically take a month for a vendor to register as a government supplier. Product category was limited. Procurement rates were rigid, fixed for one or two years, which meant government often ended up buying end-of-life electronic products. “The whole process of price discovery was opaque, static and there were allegations that suppliers would form a cartel to get the rates fixed at a certain level,” says Binoy Kumar, secretary, Ministry of Steel.

Seasoned vendors would game the system, keeping a tight control on who could supply and who could not, thus constraining vendor options. For example, there were only three vendors supplying textile clothing (used by police forces, etc). “This was shocking,” says Kumar.

Fixing rate contract for an item or a service could take up to six months. Preparing bid document was an elaborate manual process spanning three months. While product specification was not standardised, for services, consultants were hired to fix service level agreements (SLAs). Vendor payment was patchy and often prices quoted in the government could be higher than what was available outside. “Price negotiation, price discovery and vendor options were all very limited,” says Kumar.

In early 2016, the government took a decision to reform DGS&D (it comes under the Ministry of Commerce, which at the time was headed by Nirmala Sitharaman). Kumar, the then DGS&D head, took four months to build a marketplace offering one product and one service — computers and cabhiring services — as a proof of concept.

With a big thumbs up from his bosses, GeM has been steadily scaled up. In 2017, DGS&D was shut down. To help bureaucrats get on board GeM, over 30,000 training sessions have been conducted and now the training is part of the curriculum at the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration, Mussoorie. While the central government procurement has moved to GeM, both PSUs and state governments have signed on voluntarily, realising the benefits.

Government procurement broadly falls under three categories. One, direct purchase where the buyer can directly pick and order the product (of value under Rs 25,000) on GeM. Two, the Rs 25,000-5 lakh category where they need to compare offerings of at least three vendors (listed on GeM platform) and pick the one with the lowest price.

Three, the Rs 5 lakh-plus category where buyers need to invite bids to pick a vendor. The officers encountered many challenges along the way. Earlier, vendor registration and verification was physical, entailing documentation that could be over 70 pages and time-consuming, says KC Jha, ACEO, GeM. Now everything is done digitally. For example, Aadhaar is used for identification, income-tax returns and PAN for verifying the vendor’s financial worth and MCA database for verifying a company’s digital identity. With the help of Quality Council of India and local experts, video recording can be submitted to further automate verification of vendors and products.

Initially, prices on GeM were higher than, say, on Flipkart. So, they introduced a tool where prices on GeM could be easily compared with those on other ecommerce sites. “We now have a tool to predict when product prices could be too high or too low,” says Rajesh Narang, CTO, GeM. Like any digital platform, buyers and sellers here can rate each other, creating data to vet them for future orders and nudge behavioural changes.

E-Edge

The benefits have been enormous. “GeM platform is fast and time is saved in bidding,” says Jagdeep Singh, executive director (operations), RailTel Corporation of India. Chauhan, CEO of GeM, says it cut costs by about 25 per cent . As a category, automobile has been the biggest hit, with an instant 12 per cent discount. Aggregating purchase — for instance, five states together bought 1 lakh smart phones — has helped government to negotiate for bigger discounts.

Product categories have multiplied from under 400 in the early months to 3,500 now. Vendor registration time has shrunk from 30 days to under 10 minutes. Instead of procurement rates fixed for one or two years, now it’s dynamic and market-linked.

The vendor base has become more diverse and inclusive, with an emphasis on supporting startups and MSMEs. “Being a startup, we normally would not qualify for government orders. GeM has made that possible,” says Sanjay Kamra, managing director, Troika Transsolutions, a fintech and energy management startup. Sameer Jain, business development head of Nanoclean Global, a company that sells patented nasal filters that keep out air pollution, says his company got bulk orders from traffic police in Delhi and Chandigarh, thanks to GeM. “From orders to payments, everything was smooth.”

However, challenges remain. “Rates and timelines have come down and the system is stabilising but in remote areas where order is small, delivery is an issue,” says a paramilitary official who didn’t want to be quoted. “The platform needs to be made more user-friendly,” says Singh of RailTel.

There are issues around counterfeits, and GeM is working with OEMs to find ways to tackle it. Officers can flag instances of fake product delivery and after three such instances those vendors are banned. Since there is no advertising on GeM, product discovery of non-traditional products like nasofilter can be difficult.

Chauhan acknowledges the challenges but is upbeat. “It’s a journey. We are working to get better. We are at 3,000 daily transactions today and should touch Rs 1 lakh crore this fiscal. We hope to reach Rs 5-6 lakh crore within five years.”

No comments:

Post a Comment