By Andy Mukherjee

By Andy MukherjeeJeff Bezos is in India at an awkward moment. Just before his visit, the country’s antitrust authority ordered a probe into the business practices of its two main American-owned shopping websites. One of them is his.

How worried should the Amazon.com Inc. boss be?

If the Competition Commission’s recently released study on e-commerce is any guide, Bezos shouldn’t lose any sleep over the $6.5 billion he has committed so far — including $1 billion just this week — to win the only billion-person market that’s open to Western tech firms. The document, which forms the basis for the antitrust investigation, has much fodder for action, but nothing that hasn't already been chewed over.

Amazon India and Walmart Inc.-owned Flipkart Online Services Pvt. are required to be neutral online marketplaces. Sellers they own can’t offer goods on their websites. That’s the law, and sure enough, last year Bezos hastily sold a big chunk of Amazon’s stake in Cloudtail, its top Indian partner, to stay on the right side of it. Flipkart, too, found a way to tiptoe around the requirement that foreign-owned platforms only facilitate e-commerce; they aren’t allowed to control inventory or influence prices.

Yet many small retailers, who compete online, believe their products are outgunned in customer searches by preferred sellers — such as Cloudtail and Appario Retail Pvt for Amazon and OmniTech Retail India Ltd. for Flipkart — and their heavily discounted offerings. Here’s how the Competition Commission’s study frames the problem:

“The price points at which these sellers sell the products on the marketplace platforms are in many instances lower than the cost price for the brick-and-mortar retailers. These retailers maintain that, therefore, they either have to match the online discounts at a significant loss or the online market would be foreclosed for them. This was pointed out to be a particularly pressing concern in the case of mobile phones, where online markets constitute around 40% of the total sales in the country.”

With a traders’ association announcing sit-ins and protest rallies in 300 cities, Bezos understands the need to manage the anger of stakeholders in an important market. At a summit of sellers in New Delhi on Wednesday, he announced a fresh $1 billion investment to help bring small businesses online. To political authorities, Amazon wants to demonstrate the social usefulness of e-commerce by committing to export $10 billion of made-in-India goods by 2025.

Can the competition investigation upend existing business models? There’s a hint of a stick in the watchdog’s study, which notes that, “Any potentially anti-competitive unilateral conduct of platforms or platforms’ vertical arrangements with sellers/service providers will receive enforcement attention.” Yet, in closing, the commission just asks the industry to police itself by working on things like describing search-ranking parameters “in plain and intelligible language.”

It’ll be unrealistic to expect anything more dramatic from the formal inquiry. After all, the final customer isn’t complaining. She would rather receive a bigger discount on a new mobile phone than ask why it’s being exclusively sold online.

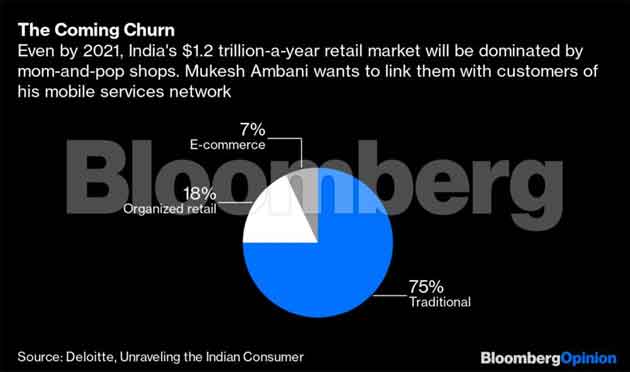

More than any antitrust order, the real challenge for Bezos will come from “phygital” retail, a combination of physical and digital commerce that Mukesh Ambani, Asia’s richest man, is currently piloting. Ambani’s ambition is to link up 30 million neighborhood stores to the 360 million-plus customers of his 4G telecom network, Jio. If he can dominate grocery and fast-moving consumer goods by offering discounts, cashless payment, in-store credit and the convenience of home delivery, small shops around the country could become one gigantic storefront for his JioMart. If they share their purchase, sales and inventory data with Ambani, they may even get to enjoy lower borrowing costs from banks and nonbank financiers. They won’t be as independent as they now are, but they will be bigger and more profitable, and more competitive against pure e-commerce.

This future isn’t too far away. The takeaway for the antitrust authority is that they can’t put up new restrictions on Amazon and Flipkart based on the 7% of a $1.2 trillion retail market that’s gone online. Major changes are afoot in the remaining 93% of the industry that’s currently offline. Wait for the churn that comes after JioMart goes live. Bezos, too, will be waiting.

No comments:

Post a Comment