At a time when Flipkart’s valuation has been marked up by one of its investors Morgan Stanley, the Indian arm of global ecommerce behemoth Amazon has reported over 105% growth in revenue in FY17.

As per filings with the Registrar of Companies (RoC), Amazon Seller Services posted a 41% increase in earning to $485.4 Mn (INR 3,128 Cr) during the said period. Amazon Seller Services currently earns through commissions, advertisements and shipping fees.

Recently, in the third week of November, Amazon India issued paid-up capital of $2.7 Bn (INR 17,839 Cr) towards its marketplace arm Amazon Seller Services, as per its regulatory filings.

Commenting on the feat, a spokesperson for Amazon said, “Comparing like-to-like, the Amazon Marketplace revenue in India grew by 105% for the year ending March 31, 2017. The Annual Returns filings include other line items.”

In addition to earnings from the marketplace and seller commissions, Amazon India currently generates revenue from its Seattle-headquartered parent by way of advertising fees, royalty on sales of Amazon’s in-house brands like Kindle and other transactions.

As per industry experts, the ecommerce giant’s impressive growth can be attributed, in part, to demonetisation which was instituted in November 2016. Speaking on the matter, an online seller on Amazon requesting anonymity said, “Last fiscal, the impact on Amazon was across categories -smartphones to electronics to apparel. These are the largest selling and fastest growing segments in e-commerce.”

According to some, however, Amazon’s growth in sales slowed down considerably after the Indian government’s Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) cautioned online marketplaces against deep discounting in April 2016.

A report by Hong Kong-based Counterpoint Research, for instance, states that the online sales of smartphones and other gadgets stagnated last fiscal after a three-year period of steady growth. Online smartphone sales increase merely by one percent to 32% in 2016, which the study ascribed to demonetisation, lower discounts and uniform pricing across online and offline platforms.

Another factor that has contributed to the slowdown pertains to the new FDI guidelines issued by the DIPP last year. Formalised in March 2016, the stricter guidelines on ecommerce dictate:

- An ecommerce entity would not permit more than 25% of the sales effected through its marketplace from one vendor or their group companies.

- Ecommerce entities providing marketplace would not directly or indirectly influence the sale price of goods or services and shall maintain level playing field.

Consequently, Amazon India’s biggest seller Cloudtail stopped the sale of mobile phones on its platform in September 2016. Prior to that, smartphones contributed towards a significant portion of Cloudtail’s revenues. As per the earning report posted recently, Cloudtail recorded a 24% jump in its revenue for FY17, showcasing a net revenue of $883.1 Mn (INR 5,688.7 Cr).

However, this is significantly less compared to the 300% surge to $712 Mn (INR 4,586.9 Cr) the vendor reported in FY16. Cloudtail currently competes with Flipkart’s biggest vendor WS Retail, which posted a net revenue of $2.16 Bn ( INR 13,921 Cr) in 2016. The financial report for FY17 has not yet been filed by Flipkart.

Most recently, with the implementation of Goods and Services Tax (GST) in April 2017, Amazon India also had to suspend its invite-only Platinum Seller Program (PSP).

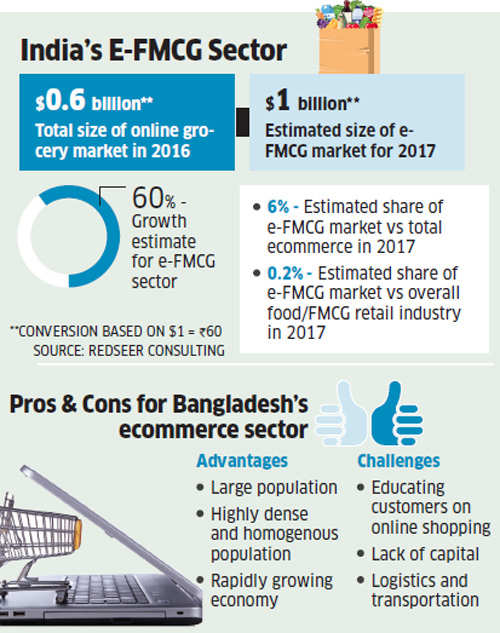

While changing regulations are making it more difficult for ecommerce platforms to sustain business growth, Amazon remains focussed on its aim to capture the Indian market. To that end, the online marketplace recently doubled its authorized capital to $4.74 Bn (INR 31,000 Cr), matching its earlier capital commitment of $5 Bn made in June last year. With the goal of getting ahead of rival Flipkart, the company is also doubling down on its efforts to diversify its business. On the one hand, it is getting ready to enter the online food retail and grocery market, while on the other hand, it is eyeing a piece of the Indian digital payments pie with Amazon Pay. The strategy seems to be working, given that it clocked over 105% growth in FY17.